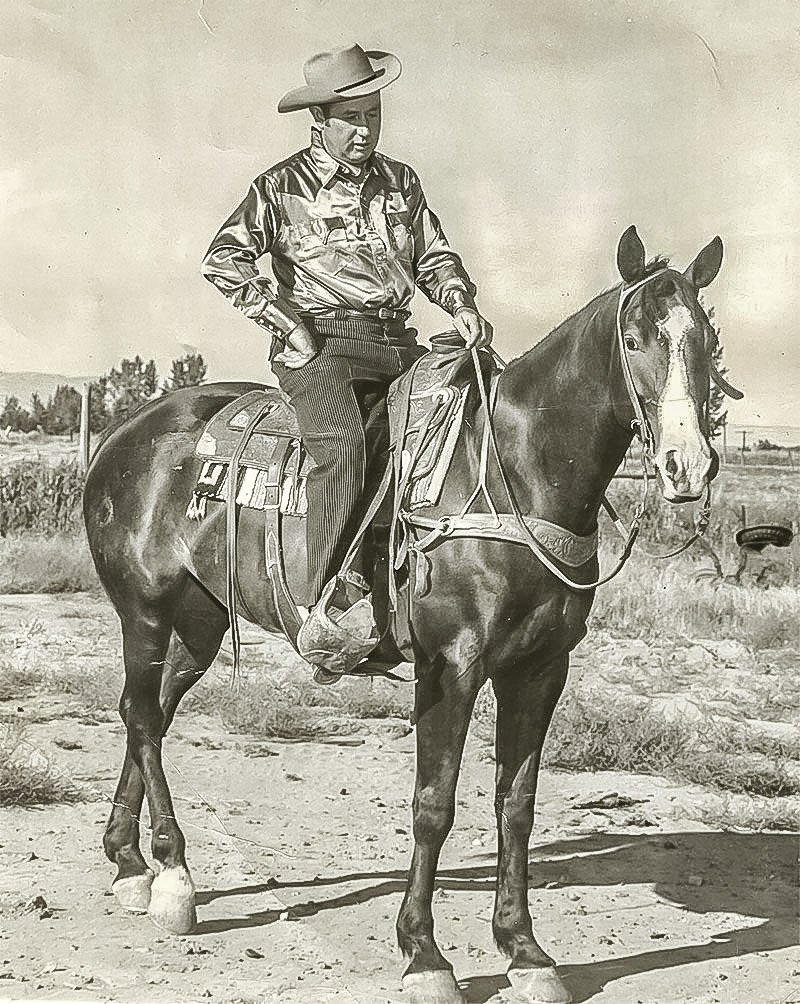

Harley Tucker: Pioneering Chief Joseph Days

In 1946, Harley Tucker played a pivotal role in the inception of the very first Chief Joseph Days, a rodeo and festival that would grow to become one of the most significant events in the Northwest. That inaugural year witnessed the rodeo's humble beginnings on the East Moraine of Wallowa Lake, where the skeletal structure of the original arena still stands as a testament to its historical significance.

Over the years, Chief Joseph Days outgrew its initial location and now finds its vibrant home at the Harley Tucker Memorial Arena in Joseph, Oregon. During the annual Chief Joseph Days, the quaint village of Joseph experiences a remarkable transformation, swelling from its usual population of 1,000 residents to nearly ten times that number.

The appeal of Chief Joseph Days lies in offering visitors an authentic glimpse of the American West, a living testament to a bygone era. Many families have been returning to this event for generations, while others journey from distant corners of the globe, including the East Coast and foreign countries, to partake in this celebration.

Harley Tucker, whose legacy is forever entwined with this rodeo, passed away in 1960. He held the distinction of being one of the nation's foremost stock contractors, supplying stock and overseeing the production of over 25 rodeos across the Northwest each year. In recognition of his contributions, Tucker was posthumously inducted into the National Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City in 1997, the St. Paul Rodeo Hall of Fame in 1999, and the Pendleton Round-Up Hall of Fame in 1980.

The Tucker family, an expansive and tightly-knit clan, has preserved the rich traditions established many years ago. Descendants of Harley Tucker, including his children, grandchildren, nieces, and nephews, have been active participants in Chief Joseph Days throughout the years. As Chief Joseph Days approaches its 67th year, it continues to exude a distinct community flavor while delivering world-class entertainment to all who partake in this remarkable Western tradition.

YOUNG CHIEF JOSEPH - LAST OF THE BIG CHIEFS

HINMUT-TOO-YAH-LAT-KEKEHT

Chief Joseph's legacy is woven into the fabric of history, and his presence endures through various commemorations. His likeness and name are ubiquitous, whether adorning a town, a hotel, a rodeo, or a mountain. In a world where countless faces and names have faded into the past, Chief Joseph's story remains indelible, a reminder of our responsibility to honor factual history and acknowledge the suffering endured by Native Americans.

Known as Nimíipuu, meaning "The People" in their native language, the Nez Perce refer to themselves by this term. Interestingly, "Nez Percé" is an exonym assigned by French Canadian fur traders who frequented the region in the late 18th century, signifying "pierced nose." However, this term is a misnomer, as the tribe did not practice nose piercing.

Chief Joseph's Nimíipuu name, Hinmut-too-yah-lat-kekeht, translates to "Thunder Rolling In the Mountains" in English. Born in 1840, most likely in the breathtaking Wallowa Valley, he grew to become a respected chief. In his later years, white settlers came to know him as "Young Joseph."

White settlers had been gradually arriving in the Valley of the Winding Waters since approximately 1834. These initial arrivals consisted of explorers, trappers, and missionaries, a mere trickle at the outset. However, this trickle evolved into a steady stream, eventually transforming into a torrent that inundated the land, erasing all that once was.

In 1855, Chief Joseph's father, recognized by white settlers as Old Joseph, entered into a treaty with Isaac Stevens, the governor of Washington. Old Joseph and several other tribal chiefs ceded a portion of the land they had long considered their own to the white settlers. Yet, they ensured that the Wallowa Valley remained under their ownership, vowing never to surrender it or sell it to "The Hairy Man" from the East.

Regrettably, the treaty of 1855, the first between white settlers and the Nez Perce, was swiftly violated. Promised annuities from the government arrived late, if at all, leaving the Nez Perce justifiably aggrieved.

In 1863, the government embarked on yet another round of negotiations. Although Old Joseph participated in these discussions, he staunchly refused to sign the treaty when he discovered that the white settlers sought control of his beloved valley. Nevertheless, others among the Nez Perce did sign, and the government laid claim to this sacred land. This treaty caused a fracture within the Nez Perce community, and ominous war clouds gathered on the horizon.

Young Joseph, growing up under the looming shadows of those gathering war clouds, faced a daunting responsibility when his father passed away. He had imbibed the teachings that upholding the treaty of 1863 would be tantamount to betraying the memory of his father. With unwavering determination, he vowed to protect the Wallowa Valley for his people, a commitment that would become the cornerstone of his leadership.

In 1871, the first white settlers made their appearance in the Valley of the Winding Waters. Having previously inhabited the Grande Ronde Valley, they sought more fertile and expansive rangeland in this new territory. These pioneers, after careful consideration, ventured forth, returned with others, and soon homesteads began to dot the landscape. However, with this influx of settlers, tensions between the white newcomers and the Nez Perce began to simmer, and the clouds of discord grew increasingly ominous.

At the center of this unfolding drama stood Young Joseph, a leader who was not a war chief but a wise statesman and an eloquent orator. Historical records reveal that he consistently urged his people to maintain peaceful coexistence with the newly arrived settlers. This period of relative harmony endured from 1871 to 1876. However, in the summer of 1876, the dark clouds of conflict began to rumble, and the first tragic bloodshed occurred.

The initial incident revolved around two white settlers, Finley and McNall, and a Nez Perce brave named Wil-lot-yah. The settlers, suspecting stolen horses, encountered a Nez Perce camp and initiated a search. A scuffle ensued, resulting in the shooting of Wil-lot-yah by Finley.

Chief Joseph and his band sought justice for this act, but it remained elusive. The two settlers were tried for the killing and, to the dismay of the Nez Perce, acquitted. Animosities on both sides escalated, and a series of further incidents deepened the divide. Ultimately, the government intervened, forming a commission to address the mounting problems in the Wallowa Valley, which recommended that the Nez Perce be forcibly removed from the region, if necessary.

Young Joseph, recognizing the unstoppable tide of events, made a heart-wrenching decision in May 1877. Contrary to his earlier vows, he led his people away from the Wallowas, directing them towards the Lapwai Reservation in Idaho, their new designated home.

Amidst this turmoil, a bitter undercurrent among some of the younger members of the band led to a tragic episode. Three of them, in a fit of rage, separated from the group and killed four white settlers on their journey. This act marked the breaking point of a storm that had been gathering for years.

Anticipating that retribution from the white settlers was imminent, Chief Joseph resolved to guide his people to Canada. He led over 800 members of his tribe in that direction, closely pursued by General O.O. Howard, a renowned one-armed Indian fighter.

The pursuit led to a grueling confrontation in Montana, specifically at Bear Paw Mountain, just 50 miles from the Canadian border, in October 1877. The ensuing battle lasted for six days, resulting in a devastating toll of 275 lives lost, including 150 Nez Perce and 125 U.S. soldiers.

After surrendering, Chief Joseph and his people were relocated first to Kansas and subsequently to what is now Oklahoma. Joseph dedicated the next several years to advocating for his people's cause, even meeting with President Rutherford Hayes in 1879. Eventually, his people were dispersed among reservations in Oklahoma, Idaho, and Washington.

The story of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce serves as a poignant testament to their enduring resilience in the face of adversity, a chapter of history marked by unwavering determination and unwavering commitment to their homeland and their people.

In 1885, Chief Joseph and a group of his people were finally permitted to return to the Pacific Northwest, marking a bittersweet chapter in their long and arduous journey. Yet, this return was far from a perfect solution. Many of his people had already perished, either from the ravages of war or the silent grip of disease. Furthermore, their new home remained miles away from their cherished homeland in the Wallowa Valley.

Regrettably, Chief Joseph did not live to witness the land of his childhood and youthful warrior days once more. He passed away in exile at the age of 64 on September 21, 1904, and found his final resting place in the Colville Indian Cemetery on the Colville Reservation in the state of Washington.

Today, Chief Joseph's memory is deeply ingrained in the tapestry of Wallowa County. His image graces local businesses, the post office, restaurants, vacation rentals, and numerous other establishments, all serving as a testament to a man who sought nothing but peace and justice for his people.

He is remembered for his poignant words: "The earth is the mother of all people, and all people should have equal rights upon it." His plea for freedom and equality resonates through time: "Let me be a free man, free to travel, free to stop, free to work, free to trade where I choose. Let me be free to choose my own teachers, free to follow the religion of my fathers, free to think and talk and act for myself, and I will obey every law, or submit to the penalty." Chief Joseph's enduring message continues to inspire and remind us of the importance of respecting the rights and dignity of all people.